This review is part of the A Play of Light and Shadow: Horror in Silent Cinema Series

Movie Review – Eerie Tales (1919)

Eerie Tales (1919) is a German film released right on the cusp of the Expressionist movement, predating The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) by only a few months, and one can clearly see German cinema moving in that direction through this movie.

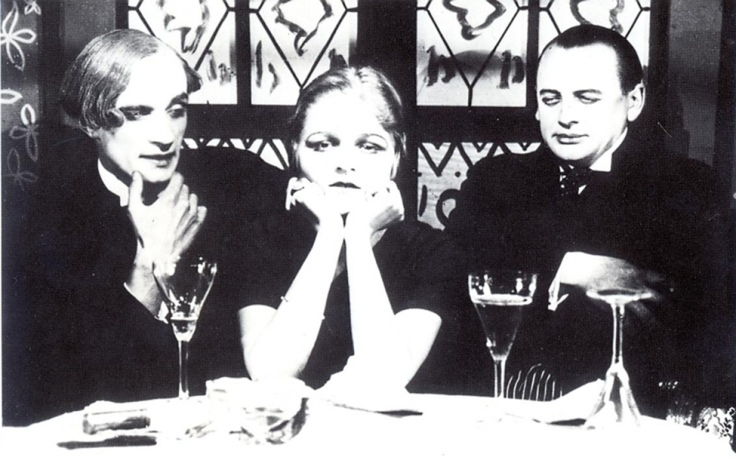

This film is one of the earliest examples of the horror anthology, perhaps even the first. The story revolves around a bookshop in which three portraits – the Devil, Death, and a prostitute – come to life and read scary stories from the stacks of books. The three main actors play both the portraits and all of the lead roles in the five stories, and they look like they’re having a blast doing so. The tone of the film is mirthful and a lot of the joy in watching Eerie Tales lies in seeing the actors trying different roles. Most of the stories are the predictable macabre tales of the time, and of course includes one by Edgar Allan Poe. As they nearly all involve a love triangle of sorts, the plots tend to blur together. The movie certainly creaks in places, but overall it’s a nicely paced romp for those acclimated to the filming styles of the time period, particularly the limitations.

Like with The Student of Prague (1913), gaining insight into the people involved makes the work more pleasurable to watch. Their stories tell a great deal about Germany between the wars, and their individual lives are generally fascinating. First is the film’s director, Richard Oswald, who would over the course of his career direct over 100 pictures (he was more prolific than good, unfortunately). Most significantly, in the same year he made Eerie Tales, he also directed the profoundly important Different from the Others, featuring the first gay character written for cinema. What makes this film so amazing is that the portrayal of the homosexual is entirely sympathetic. Not surprisingly, the Nazi censors would end up destroying most copies, but fragments do still exist. When the National Socialists overran Austria, Oswald, being Jewish, fled to America and had a waning career in Hollywood.

And who played the gay character in Different from the Others? None other than Conrad Veidt, who plays Death in Eerie Tales and who is one of my personal film heroes. Truly, Veidt is the only actor that can rival Lon Chaney in his work in silent horror. Fascinated by acting at an early age, he hid his passion from his disapproving father but was quietly encouraged by his supportive mother. In World War I he took part in the Battle of Warsaw but contracted jaundice and pneumonia. After recuperating he was still deemed physically unfit and was discharged from the army, and so he tried his hand at theater, eventually being hired as an extra by the renowned German Theater run by Max Reinhardt. His skills were quickly recognized and his roles increased. He made dozens of films, including of course Eerie Tales, before getting his international breakout role as Cesare in Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). He would become the second-highest paid actor in Germany (behind Emil Jannings) and star in the horror films Waxworks (1924), which won him the admiration of American actor John Barrymore, The Hands of Orlac (1924), The Student of Prague (1926), and Paul Leni’s American masterpiece The Man Who Laughs (1928), which would inspire Bob Kane to create the Joker.

Committed to tolerance and liberalism, Veidt was a staunch anti-Nazi and outspoken enemy of Hitler. Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, recognized his value and offered an Aryan certification to his half-Jewish wife if he would sign an oath of loyalty. Veidt refused and tried to leave for England but was placed under house arrest by the Gestapo and even ordered executed, but was eventually allowed to leave in order to avoid an international incident. Though not Jewish, once arriving in Britain he signed his religious affiliation as “Jew” and made a pro-Jewish film, thumbing his nose at his homeland’s anti-Semitism. In the era of talkies Veidt’s accent meant that he would be offered many roles playing Nazis, most notably in Casablanca (1942), and he had no qualms about taking them and revealing the horrific nature of the National Socialists. All the while, nearly all the money he made would go to the British war effort. Tragically, he died suddenly of a heart attack on a Hollywood golf course at the age of 50. In the 1920s he was known in Germany as the “Demon of the Silver Screen,” but in addition to being a brilliant actor Veidt was a true hero at a time when such moral fortitude was most needed yet was in such short supply.

The second male of the film’s acting trio playing the Devil is Reinhold Schunzel, who would go on to direct extremely popular films in Germany, so popular that despite his Jewish background the Nazis would name him an “honorary Aryan,” meaning they wouldn’t kill him if he kept making good films. That wouldn’t stop them from interfering, and in 1937 he went to Hollywood where his directing career sputtered. He eventually went back to acting, but after the war he carried the stigma of having stayed and worked in film with the blessings of the Nazis and found work increasingly hard to come by.

Lastly we have the role of the prostitute, and for Anita Berber the part probably wasn’t a stretch. During the 1910s Berber became a popular exotic nude dancer and quickly made a reputation for herself as a voracious lover of men and women. She became the embodiment of Berlin’s debauchery during the Weimar Republic. Many today would never believe that before the Nazis rose to power Berlin was arguably the most liberal and hedonistic city in Europe, mainly a result of the postwar economic downturn attracting foreigners with money looking for fun. Berber obliged. She was known to perform stark nude, the dances named after amphetamines, and was often seen walking around Berlin with her pet monkey wrapped around her neck. Marlene Dietrich could be counted among her lovers. She continued to dance throughout the 1920s while imbibing in copious amounts of alcohol and cocaine. Those substances would rack her body and, like the original candle in the wind, she would die of consumption by the age of 29 in 1928, but not before she would be captured for posterity in a famous painting by Otto Dix in 1925.

On its own, Eerie Tales is a middling effort. But knowing the performers elevates the experience, at least for me. It’s great to see these people working together with such clear bacchanal joy, especially knowing that the dark cloud of fascism is moving ever closer and that so much of what they embody would no longer be tolerated, including tolerance itself.

Oswald would flee. Veidt would defy. Schunzel would collaborate. And Berber would burn out as a symbol of a dying age. Eerie tales, indeed.

Grade: C+

October 28, 2015 at 2:11 am

I do love this movie so much–it’s a great little Halloween romp. Thanks for giving good information on the actors as well; I hate it when people claim Berber as a lesbian or Veidt as gay or straight when both were bisexual, so a big thumbs up from me for that. Different From the Others was dangerous for Veidt in particular, as his bisexuality was pretty much an open secret, and when the Nazis detained him, they would’ve known about that, as did most of Berlin–I shudder to think at what happened during his incarceration. He is my favourite actor of all time because of his incredible bravery and of course, talent. And oh, hey, I didn’t know Schunzel was Jewish, so that was interesting to find out–thanks for putting that in. Nice article; shall share it with my friends.

LikeLike

October 28, 2015 at 2:23 am

Thank you for the comment. It’s been fascinating exploring this era of cinema. Veidt is certainly worth the admiration, both for his talent and for his ethical fortitude – the fact that he worked so extensively in horror is an added bonus for me, personally.

LikeLike