This review is part of the A Play of Light and Shadow: Horror in Silent Cinema Series

Movie Review – The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

From July 1914 to November 1918 the Great War raged – a tantrum of metal, fire, and pride that rent the earth and chewed flesh. A generation of men would be decimated, their views about life, government, authority, and mortality inextricably altered. Gone were the delusions of glory and nationalism and the jingoistic jingles to which they marched to the front. By the end more than nine million combatants and seven million civilian lay in graves, many unmarked. Anyone who reads the literature of this period, from Erich Maria Remarque’s unforgettable All Quiet on the Western Front to the potent poetry of Wilfred Owen, cannot but feel overcome with the profound sense of bitterness and betrayal these men felt toward society, authority, and their own families. The French war drama J’accuse (1919) dealt with this directly by depicting dead soldiers rising from the battlefield to confront their families and neighbors for their complicity in the war. Such resentment was felt by both sides.

The Parable of the Old Man and the Young

So Abram rose, and clave the wood, and went,

And took the fire with him, and a knife.

And as they sojourned both of them together,

Isaac the first-born spake and said, My Father,

Behold the preparations, fire and iron,

But where the lamb for this burnt-offering?

Then Abram bound the youth with belts and straps,

and builded parapets and trenches there,

And stretchèd forth the knife to slay his son.

When lo! an angel called him out of heaven,

Saying, Lay not thy hand upon the lad,

Neither do anything to him. Behold,

A ram, caught in a thicket by its horns;

Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.

But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.

– Wilfred Owen (1918)

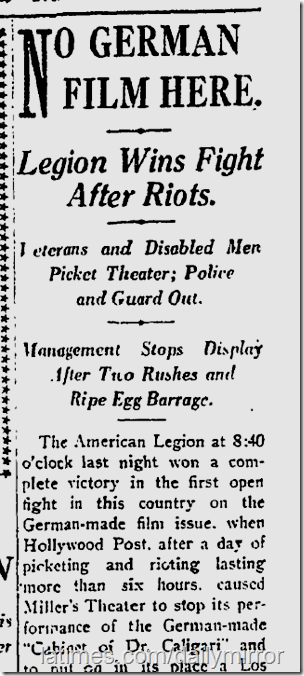

In the spring of 1921, though the war was over, American anger was still fresh, particularly toward the Germans. Veterans, many of them baring the tell-tale marks of battle-born disfigurement, marched on Miller’s Theater in Los Angeles to protest the opening of a German film for which the theater advertised, with a signature from the owner scrawled upon it, as “a fantastic European picture, which will… undoubtedly have a significant effect on American methods of Production. It brings to the screen an absolutely new technique, and its influence, I believe, will be tremendous.” For the protesters, it was not just that the film was German was their anger fueled, but also the implication that it was superior to America’s offerings. In the end the protesters won and Miller’s Theater pulled the film, but it was eventually shown in Los Angeles five years later when tensions had cooled. Nevertheless, 1920’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was a film that changed cinema forever.

As cultural historian David J. Skal writes in The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, “It is difficult to overstate the kind of revelation Caligari represented to much of its audience, which felt it was witnessing an evolutionary leap in cinema, one comparable to the coming of sound…” for it was a film that “reconfigured the possibilities of space and form for the general public” (Skal, pg. 39). The movie hit contemporary critics like a gut-punch, exciting them to new possibilities in movie-making (and established countless precedents that the horror genre is still mining today). This new approach was as much a psychological reaction from the Great War, which will be discussed below, as it was a calculated move for German filmmakers who sought a style distinct from Hollywood, against which it knew it could not compete on equal terms with similar movies. As Erich Pommer, head of the Decla Bioscope production company which made Caligari, once explained:

“The German film industry made ‘stylized films’ to make money. Let me explain. At the end of World War I the Hollywood industry moved toward world supremacy… Germany was defeated; how could she make films that would compete with the others? It would have been impossible to try and imitate Hollywood or the French. So we tried something new: the expressionist or stylized films. This was possible because Germany had an overflow of good artists and writers, a strong literary tradition, and a great tradition of theatre. This provided a basis of good, trained actors. World War I finished the French industry; the problem for Germany was to compete with Hollywood” (as quoted by S.S. Prawer, Caligari’s Children, pg. 165).

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is not only the first great horror film; it is also the first German expressionist masterpiece. Expressionism was an artistic movement which emphasized the portrayal of emotion over realism, and was largely a reaction to the contemporary popularity of Naturalism and Impressionism. Heavily influenced by such works as Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” expressionists blurred the lines between what is real and what is conceptual, often offering distorted visions of people and their environment. What they created is both beautiful and inherently grotesque. As German cinema began to adopt the style, with inklings to be found in 1913’s The Student of Prague, the subject matter became necessarily cerebral, and the skewed perspective naturally horrific.

The highly stylized expressionist movement in Weimar Republic cinema, with its absurdly piercing angles, bold shadows, and leaning architecture that looks poised to crash down upon the inhabitants, was born as much by necessity as by creativity. As the Great War engulfed Europe, Germany banned all foreign films, creating an exclusive domestic market for its films. Due to effectively non-existent budgets and unreliable electricity, the closed sets had to be controlled. Instead of creating shadows with light they painted them in broad strokes that stabbed at the rest of the scenery. The themes of expressionism often understandably dealt with madness and matters of the psyche, as Germany particularly had just witnessed a war-torn world seemingly gone insane. Haunted by war, the film opens with the lines: “Spirits surround us on every side… they have driven me from hearth and home, from wife and child.”

The roots of silent horror drink from many wells, with the Gothic literary tradition being the most obvious. However, less discussed is the role played by carnivals and their macabre attractions. Customers would pay to see the grotesque and the deadly, from the prevailing freak shows to a young Tod Browning’s own act of being buried alive for up to two days at a time, coining himself “The Hypnotic Living Corpse.” It is from this tradition that Caligari’s script, written by Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer, partly takes inspiration, as we see the unhinged Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss) present his somnambulist sideshow of the hypnotized Cesare (Conrad Veidt). It would also not have been forgotten by contemporary filmgoers that movies were once the subject of side-show curiosities, much like Cesare. Janowitz was also inspired by a macabre event in his life which occurred just before the war. He had been attending a fair and spied a beautiful girl. He was searching for the girl he had only glimpsed when he thought he heard her laughing in some nearby bushes. Suddenly, the laughing stopped. A man step out from the bushes and he briefly saw the shadowy face. The next day he saw a newspaper article recounting sexually tinged homicide of a girl at the fair and attended the funeral to see it was the same girl he had been admiring. There he saw the man who had stepped from the bushes, and the man seemed to recognize that Janowitz had spotted him. This eerie event lingered in Janowitz’s mind for years as he wondered how many murderers, if indeed this man was one, roamed free.

Janowitz and Mayer both became pacifists due to their experiences in World War I. Janowitz served as an officer in the Germany infantry regiment. Mayer’s early life had been tough – his father was a chronic gambler who committed suicide when Mayer was sixteen, leaving him to care for his younger siblings – and when the war arrived officials forced him to undergo traumatic psychiatric examinations to determine his fitness for service. Both gained a healthy distrust for those to whose will they were supposed to bend. Unsurprisingly, the script they conceived presented an image of authority drunk with power, sending a sleepwalking soldier to do its killing. The metaphor for the soldier’s experience, and the way they felt used by those they trusted, is apparent, even if it was clearer in hindsight than it was to them when they wrote it. As Janowitz would write: “It was years after the completion of the screenplay that I realized our subconscious intention… The corresponding connection between Doctor Caligari, and the great authoritative power of the Government that we hated, and which had subdued us into an oath, forcing conscription on those in opposition to its official war aims, compelling us to murder and be murdered” (as quoted by Steve Haberman, Silent Screams, pg. 36).

Fritz Lang was first signed on to direct the film and supposedly (accounts seem to differ) it was he who suggested the famous “twist” framing story – revolutionary for its time – of a mad man recounting his delusions. Sigmund Freud and his influential psychoanalysis, it may be noted, were then experiencing their heyday. Janowitz and Mayer claim to have protested the change, believing it diluted their pacifist message by revealing the maliciously insane authority to be the mere ravings of mad man. The writers appear to have been justified in their criticism for contemporary audiences focused on this later mental aspect, yet it also appears to have allowed them to more easily swallow the radically expressionist sets, performances and narrative. The anti-war message appears to have gone unnoticed, at least upon its initial release. Regardless, Lang left the project and Robert Wiene signed on, keeping the new framing story intact.

However, the framing device does not discount the cautionary symbolism of the film, it merely adds another level of unease, inviting the audience to question their own perceived reality. Additionally, these story elements are there for a reason, no matter what twist comes in the end. To illustrate by way of a more popular and beloved film, Dorothy awaking with her family around her bed does not make the messages about friendship, self-worth, and appreciating one’s home now null and void. Even in delusions and fantasies can valuable lessons be learned.

It must also be recognized that the film’s last scene hardly lets the audience off the hook. The naturalistic framing scenes in the garden provide a contrast to the expressionistic visions of Francis’s insanity, which the audience has been made to share, but the cell in which he is placed at the end is identical to that which he envisioned in his supposed delusions. Add to this the last long shot of the film as the camera stays upon Werner Krauss’s face, where once we knew him as the insidious Caligari he has now been revealed to be the asylum’s supposedly benevolent director. Yet the look he gives is unfeelingly eerie, leaving the viewer to once again question his motives, his sincerity, and whether or not Francis was right all along – or whether we have not come to share Francis’s own paranoia. Perhaps it even serves to challenge the audience: Would you recognize insane authority, even if it’s staring you in the face? Is the destruction of evil authority merely an illusion, and do we actually remain beneath its boot-heel? Furthermore, the ambiguity of what we have witnessed serves to add a layer of paranoia as we’re compelled to ask if the hero who we’ve invested in is the true danger, or has our only hope been made impotent by the real threat? All these questions conspire to create unease, and they reflect with distorted clarity the anxieties and wounds of the era. As S.S. Prawer succinctly writes in his examination of the film’s terror iconography:

“[We may consider] the profound disorientation the film conveys, the questions it leads us to ask about authority, about social legitimation, about the protection of society from disrupting and destructive influences, and about the shifting points of view that convert enemies into friends and friends into enemies, whose origins may well be sought in the German situation after the First World War. Like any genuine work of art, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari has its roots deep in the society of the time; but its significance, its appeal, and its influence far transcend its origins” (Caligari’s Children, pg. 199).

Wiene had directed Conrad Veidt’s first known appearance on screen in the 1917 horror film Fear, which deals with similar themes of madness, though most of his films up to this point had been dramas and comedies. Nevertheless, watching The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari – whose sets were designed by Hermann Warm, whose oft-cited credo was that “the cinematic work of art must become a living picture,” and influenced by the stage work of Max Reinhardt (of whom many of the film’s actors were former students) – is like watching a disturbing dream. Indeed, when I look back on it now I remember it like it was a dream of my own. The actors move through the surreal landscape, moving intentionally unnaturally, like ghoulish porcelain dolls. Conrad Veidt as the sleepwalking Cesare looks like he belongs in this nightmarish world, unnerving viewers as he slowly awakens and stares into the camera with his wide, expressive eyes. And yet Veidt is able to retain sympathy for the somnambulist assassin, no doubt influencing the pitiable monsters which would follow in the decades to come.

The other performances, particularly by Werner Krauss as the titular Caligari and Lil Dagover as Jane, are equally strong. Krauss’s look was inspired by a photo of an elderly Arthur Schopenhauer, whose philosophical pessimism and belief that humans were driven only by their own basic desires fits well with Caligari’s own selfish motivations.

Robert Wiene would create two more horror films, the largely forgotten Genuine, filmed the same year as Caligari, and 1924’s The Hands of Orlac, which also stars Conrad Veidt, and he would find success with many non-genre films. In the 1930s he left Germany, never to return, though it’s unclear if his reasons were political. He would die of cancer in 1938.

Hans Janowitz would retire from the film industry in 1922 and go into the oil business, eventually moving to the United States. Carl Mayer would write many other successful film treatments, including 1921’s The Haunted Castle, directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, and Murnau’s American work, the brilliant drama Sunrise (1927). Being a Jew and a pacifist, he fled to England to escape the Nazis but anti-German sentiments meant he could not find adequate work in the film industry. He died of cancer in 1944 practically penniless. His epitaph reads: “Pioneer in the art of the cinema. Erected by his friends and fellow workers.”

Werner Krauss specialized in playing villains, both on stage and in film. He appeared as an antagonist in Paul Leni’s Waxworks (1924) and in 1926’s The Student of Prague, both of which also starred Conrad Veidt. However, unlike Caligari’s pacifist writers or co-star Veidt’s defiant anti-Nazism, Krauss was an outspoken anti-Semite and supporter of the Third Reich, becoming a cultural ambassador for Nazi Germany and specializing in playing cruel Jewish villains. This is ironic as Veidt, who fled Germany and supported the war against Hitler, spent much of his later career playing Nazis in American and British films. The late Oxford scholar S.S. Prawer, whose own family fled to England to escape the Nazis in 1939, found an interesting insight into these two great actors’ on-screen choices that’s worth pondering, suggesting that each man donned the monster mask they feared the most. As he states:

“It is perhaps not without significance that of the two masters of macabre acting who combined their talents in Caligari Werner Krauss stayed in Germany during the Second World War and played a whole congregation of uncanny Jews… while Conrad Veidt went to Hollywood where the parts he was given included the sinister Nazis he played so well… In real life, of course, as these very performances serve to show, it was Werner Krauss who sold himself to the Nazis and Conrad Veidt who shared the lot of German Jews that managed to escape the holocaust. Some of the most effective screen performances may thus be seen as projections of inner fears and loathings, or of usually invisible aspects of their personality by the actors, as well as the writers and directors, of a given film” (Caligari’s Children, pg. 62).

After the war Krauss was banned from acting and forced to undergo de-Nazification. He died in Austria in 1959. (For more on the life of Conrad Veidt, see my review of 1919’s Eerie Tales.)

What The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari deals with is madness, abuse of power, and the ways in which people might be compelled to circumvent their better nature and commit acts of murder. It became the subject of 1947’s From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film by Siegfried Kracauer, the first truly influential study in German film. Kracauer’s argument was largely teleological, arguing that one could see the coming of the Nazis through an examination of films from the Weimar Republic. Unfortunately, his reasoning is often undermined by his fuzzy recollections of the films (which he would not have had readily available to him) and by the subsequent findings of evidence that run counter to his claims. Nevertheless, he recognized the symbology of Caligari which affected Germans at the time and saw what the film said of their fears and anxieties. Fortunately, the twist only slightly softens these aspects while serving to explain the dreamlike quality of the film.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari transformed cinema in immeasurable ways, spreading its influence through generations of artists, musicians, and filmmakers. Even the late David Bowie in his last music video, “Lazarus,” evoked the film. We see Bowie dressed similar to Cesare, making exaggerated gestures in the way some silent film stars acted broadly, and in the end retreats into a wardrobe that looks eerily like Cesare’s box. These allusions and more are difficult to miss and impossible to dismiss, and what Bowie meant by them may be interpreted differently by individual viewers. Nevertheless, it proves that The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari still has the power to create unease and to fascinate, and the questions it raises, along with the disturbing answers it suggests, have lost none of their importance or potency.

Grade: A+