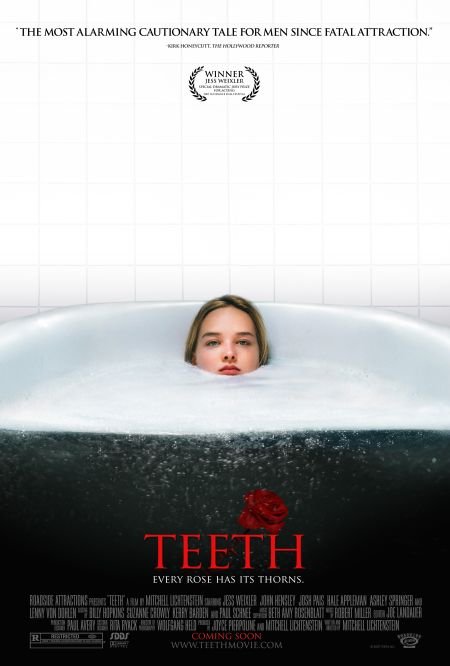

Movie Review – Teeth (2007)

(Oh-oh here she comes)

Watch out boy, she’ll chew you up!

(Oh-oh here she comes)

She’s a maneater!

– “Maneater” (1982) by Hall & Oates

Vagina dentata – this Latin expression for “toothed vagina” is found in myths across the globe and is generally thought to stem from a fear of sexual intercourse, whether as a man entering an alien place where a piece of himself is left, or as a woman fearful of injury or rape. Female biology, for the vast majority of human history and unfortunately in some communities still today, was a source of mystery. As we all know, the woman’s sexual organs are on the inside, not exposed like a man’s. Therefore people asked: What could she be hiding? Why does she bleed each month? What mysteries are at the root of her ability to create and pass life through her body? Lack of scientific knowledge, coupled with age-old superstition, is at the root of the idea that a woman can house teeth in her vagina, ready to devour any man’s denim bulge who might be seduced into her hungry fly trap.

While female biology is little mystery to most modern Americans, or should be, there are still conservative segments who believe such knowledge is damaging to maturing teens, leading to temptation and spiritual corruption. They champion abstinence-only education and such puerile gimmicks as purity rings, despite a wealth of evidence that suggests such an approach is not only less effective in preventing unwanted results such as teen pregnancy, but may in fact help contribute to it.

Such a person is the central character to 2007’s Teeth. Dawn O’Keefe (appropriate last name), played by Jess Weixler, is a Christian creationist teen who is committed to saving her virginity for marriage and who champions purity rings at church youth groups. Her own body is an enigma and when she’s raped by a trusted love interest she finds that she possesses a special biological adaptation that quickly puts the forced entry to a mangled end. Such a situation is repeated throughout the film, giving the viewer many shots – mostly darkly humorous – of severed penises and shocked males holding their bloody, emasculated stumps.

As a male viewer this is horrifying stuff, but the film is filled to the brim with guys who want to take advantage of her so there’s no end to the justification for her castrations. Dawn goes from naïve innocent to feminist vigilante, embracing evolution and her own sexual prowess along the way. The depiction of men is decidedly negative – I half-expected her step-father, the only half-way decent guy in the film, to try to molest her, so prevalent was the male misogyny – and the film might have been better served to at least have one sympathetic young male to relate to, or a positive male sexual role model to at least let the audience know that they exist. Certain characters were arguably not entirely deserving of the level of malice she bit into them, though they were not at all sympathetic.

Despite this quibble, Teeth is elevated by a strong performance from its lead. Weixler plays the role just right, from perky good-girl teen to horrified man-eater to confident man-devourer.

Writer and director Mitchell Lichtenstein smartly infuses his movie with black comedy and symbolism. Of the latter, there are the many references to serpents, which represent not only Satan’s temptation of Eve (“the serpent beguiled me and I ate”), signifying her drift from Christianity, but also Medusa, as Dawn herself becomes something that can be considered gorgonesque. As a visual metaphor, the cave opening in which she first discovers her power is dripping with toothy stalactites. An environmental message seems to also be at play. We repeatedly see two huge breast-like smoke stacks continually spewing smoke into the air. We can surmise that this is the source of Dawn’s mother’s cancer, and perhaps the cause of her mutation as well.

There were some choices made by the filmmaker that had me scratching my head. The cinematography is sometimes grainy, as though scenes were lightened significantly in post-production. Also, we see a lot of chewed man-meat, but despite the film partly addressing society’s fear in even acknowledging basic female biology (such as the anatomy textbooks having stickers covering the vagina), her weapon is never brought into the light. I am not saying this is a bad choice, but it is perhaps an odd one that undermines at least one of the film’s messages. Nevertheless, Teeth is a smart, funny, and entertaining film that will likely resonate with most women, but is a movie that guys should be sure to see too.

Grade: B-