Movie Review – Crimson Peak (2015)

In an early scene in Guillermo Del Toro’s Crimson Peak (2015), our American heroine, Edith Cushing (Mia Wasikowska), is trying to write a novel which someone casually dismisses as a ghost story. “It’s not a ghost story,” she tells him, “it’s a story with ghosts in it.” The same description can be applied to the film’s approach to the supernatural. As Cushing states in the opening, “Ghosts are real. That much I know.” This is less an indication of what is to come for the audience, who would be justified in anticipating a story infested with malevolent entities, and more of a statement of fact. In Cushing’s world ghosts exist and they sometimes interact with mortals, just as her inky mother visited her as a child and cryptically warned her to stay away from Crimson Peak. Ultimately, however, in this tale they are peripheral – truly, the plot would still stand if the ghosts were removed.

Ghosts are not the point, yet they are also not the gratuitous window-dressing their inclusion may at first appear to be. Cushing says that in literature they are metaphors for the past, and that is to some extent true for this treatment of them, though Del Toro’s preoccupation with moths and butterflies in the film could offer another. The ghosts may be the past coming back to haunt our central character, but they come equipped with knowledge of the present and future. In one scene, as Cushing and the mysterious Lady Lucille Sharpe sit in the park they view butterflies dying in the sun and note at least one particular cocoon. Perhaps death is simply a metamorphosis to an altered state, yet like these butterflies the spirit cannot live in the open. Nevertheless we later see dozens of moths thriving in an attic – the home is the place for the dead, if our centuries of stories are any indication.

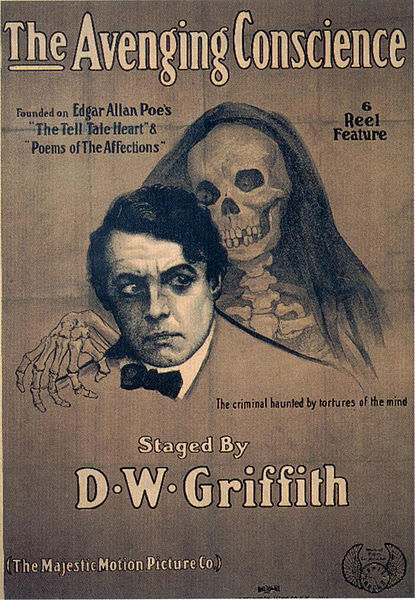

Those going to see Crimson Peak expecting a fast-moving modern horror will likely leave the film feeling underwhelmed. The film is a gothic romance, through and through, and is an ode to the gothic writers of the nineteenth century. Set in the last years of the Victorian era, Del Toro takes Cushing from Edith Wharton’s New York high society backbiting to a veritable House of Usher oozing with blood-like red clay. It is the stuff of what Edgar Allan Poe’s contemporaries called “German tales,” where the horrors weren’t the figments of imagination, but real and dangerous. Victorian literature rears its head as Cushing notes a copy of Arthur Conan Doyle on a bookshelf, foreshadowing her own detective work later in the film as she begins to realize the danger in which she has placed herself. I almost wish there were more of these literary nods for I could easily see Cushing being a variation of Jane Austen’s Catherine Moreland from Northanger Abbey (1817), who is so taken with gothic literature that she immediately suspects the worst when first inside an actual, though entirely benign, medieval abbey. Austen’s story was satire (though she personally loved the gothic genre), yet I could imagine Cushing being more mentally prepared for the agitated spirits and murderous mysteries she encounters due to her familiarity with the gothic genre, like the Victorian equivalent of meta-horror in the vein of Scream (1996). To emphasize her as a romantic, rather than a budding logician, might have better served to explain her willingness to be swept away in the more macabre circumstances.

Crimson Peak is not a film in a rush to tell its story. It’s in no hurry to leave the exquisite sets and impressive period wardrobe that the camera picks up in rich detail. The house is a character unto itself, built whole for the film. While the story looks two centuries back for inspiration, the color palette and general mood look to the period films of 1960s Hammer Film Productions (Cushing’s last name is likely an homage to Hammer’s Peter Cushing) and to the vibrant reds of Italian filmmakers like Mario Bava or Dario Argento. Similarities could easily be made, in period and visual style, with Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), though Crimson Peak is in many ways less surreal and more grounded than that film. Nevertheless, Del Toro doesn’t always allow logic to get in the way of his images and gives his imagination relatively free reign, particularly in the aspects of the crumbling estate as red clay flows continuously like blood down the walls or snow falls dreamlike within the house through a hole in the roof. Del Toro’s approach is a conscious contrast to modern horror. He attempts to make horror big both in budget and in ambition again, and perhaps also more respectable to the general audience who may be more forgiving of its horrific qualities if they can get lost in a compelling tale. The story, which was co-written by Matthew Robbins, is not one that will hold many surprises for most experienced viewers, but for those with a fondness for gothic romance there is a great deal to appreciate and respect about Del Toro’s loving treatment of it here.

For all the nostalgia at play, Del Toro’s take on the centuries-old genre is still decidedly modern. Firstly, the gore is consistent with today’s tastes. Del Toro doesn’t let the camera look away from the more uncomfortable and brutal acts of violence, shown in patient, painful detail. Secondly, Del Toro reverses traditional gender roles where men can now be the weak and manipulated sex and women can be dominant, smart, and capable of saving themselves. Gothic romance generally emphasized the female perspective, illuminating fears of patriarchy. Crimson Peak does this too and attempts to infuse its female character with a strong dignity. All in all, it becomes that rare breed of horror film, in a genre dominated by boyish sensibilities, which seeks to attract and focus upon the perspective of the female audience.

The cast is solid, particularly the macabre siblings Sir Thomas Sharpe and Lady Lucille Sharpe, played by Tom Hiddleston and Jessica Chastain. Hiddleston manages to evoke despicability and sympathy in equal measure, and Chastain is perfectly cold and unhinged.

My lone complaint of the film, and it is one on which much of the film unfortunately relies, is the central character of Edith Cushing. She is thoroughly likable and Mia Wasikowska does a fine job in her portrayal, but she lacks a story arc. The head-strong, intelligent woman we see in the beginning is the same head-strong, intelligent woman we see at the end, albeit bloodier. Her single weakness was the desire for her writing to be accepted, but this plot-line ceases half-way through the film and should have come into some significance before the end. She is a surrogate for the viewer and sometimes feels like little else.

Considering his stellar output, it is not a great criticism to say that Crimson Peak is not Del Toro’s best film. For my money, that is still 2006’s Pan’s Labyrinth. However, it is thus far his best English language film, and that indeed is saying something. Crimson Peak is Del Toro the auteur returning from his big budget forays, and if those who watch it know what they’re getting into and allow themselves to be swept down the dark, dank corridors of a bygone era, filled with the suffering cries of restless dead and the malicious secrets of the living, the experience is a rewarding one.

Grade: B