This review is part of the A Play of Light and Shadow: Horror in Silent Cinema Series

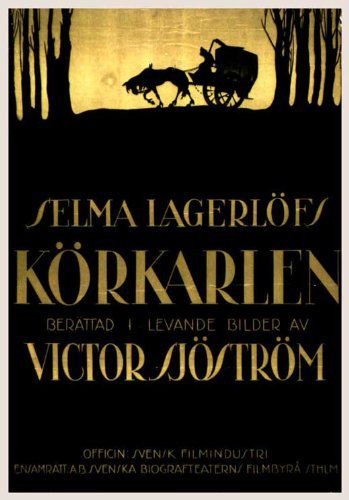

Movie Review – The Phantom Carriage (1921)

Adapted from the novel Körkarlen (1912) by Nobel prize-winning Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf, The Phantom Carriage (1921) is a Swedish fantasy-horror which had a profound influence upon subsequent filmmakers – the axe-chopping sequence would go on to influence Stanley Kubrick in The Shining (1980) and Ingmar Bergman considered the movie a prime inspiration and even cast the film’s director, Victor Sjöström, in his 1957 Wild Strawberries, considered one of Bergman’s best films. Sjöström had previously made outdoor dramas, and both the content and the studio-bound approach to the filming of this piece, necessary due to the complicated special effects shots and desired deep focus, was a significant departure for the director – and one which paid off in spades.

Appropriately released on New Year’s Day in 1921, the plot revolves around a rotten drunkard named David Holm who is killed at midnight on New Year’s Eve, now condemned to become Death’s servant. For a year he must drive a ghostly horse-drawn carriage, collecting the souls of the damned. However, the previous driver for whom he is taking over was an old drinking buddy who helped lead him astray, and, like Marley to Scrooge, Holm is shown the havoc and sorrow his actions have caused and all the opportunities for redemption he dismissed.

Sjöström, who plays Holm, gives an excellent naturalistic performance. He easily inhabits the role as do the other cast members. There’s very little of that broad overacting often found in silent films. Insight into the director’s personal history may provide deeper understanding of both his approach and his profoundly convincing, touching portrayal. As Paul Mayersberg, in his Criterion essay, writes of the performance:

“Coming from the theater, Sjöström nonetheless rejected traditional stage acting as detrimental to films. He wanted another style of performance since the dialogue could not be heard, concentrating on face, movements, and gestures. His own performance in The Phantom Carriage avoids melodrama by admitting David’s inner confusion, which simultaneously erupts into violence. His outward realism explores inner states. Some of the intertitles are actually voice-over, as he talks to himself…

In 1881, as a small child, Sjöström went to America with his father, Olaf, and mother, Maria Elizabeth, to whom he was devoted. Tragically, she died when he was seven… Olaf was a womanizer, twice bankrupt, and a born-again Christian. In 1893, Victor was returned to Sweden to live with his aunt… All his life, Sjöström feared becoming like his father, whom he closely resembled physically… Perhaps his rendering of David’s alcoholism derived from the tensions in Sjöström’s relationship with his father. His performance is so realistically and subtly detailed that it may have come from precise memories, a ghostly reincarnation of his father.”

Perhaps due also to his father’s religiosity, Sjöström is careful to avoid overtly religious moralizing and divine intervention. His intercessor is his old friend, the current Death’s assistant. Despite this, the film was re-cut when released in America to appear more as a Christian morality tale. There nevertheless remains a diabolical element, for

“The Phantom Carriage is at root a Faustian tale, with drink as the devil. If the film were the work of a Jansenist Catholic like Robert Bresson, David’s suffering would be a struggle with God’s design for him, alcohol being the mysterious presence of the divine in his bloodstream, and would probably end in suicide. But for Sjöström, God helps those who help themselves. There is an extraordinary moment when David’s wife faints out of fear at his ax attack and he fetches her a cup of water, only to berate her violently when she recovers consciousness. Here is a glimpse not of God but of a good man within a bad man. Sjöström the actor marvelously conveys the brutish, the melancholy, the sarcastic, and the reflective aspects of his character… Sjöström’s David is a study of tortured self-humiliation.”

The cinematography is beautiful and wonderfully lit, again thanks to the director’s choice in filming in a studio (the story’s author, Lagerlöf, had come into conflict with him when she originally insisted on filming in the town where the tale was set). Some scenes are truly haunting, such as that of Death’s servant retrieving the soul of a drowned man from beneath the murky sea. Likewise, the costumes are rich and the sets are appropriately claustrophobic. Sjöström’s directing is confident and the editing moves the story along smoothly.

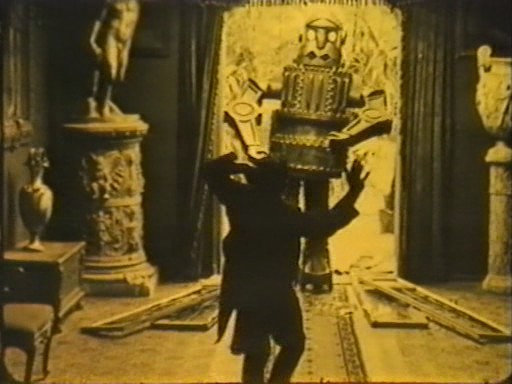

The script is tight and sophisticated, even employing flashbacks within flashbacks, which was an advanced storytelling technique for the time. The extensive special effects of the semi-transparent ghosts are particularly impressive when one considers that the double exposures were done in-camera, which had to be hand-cranked at exactly the same speed so as to appear natural.

Though the ghostly carriage is a spooky sight, the actual horror of the film lies in the actions of the living. Holm is at times unstable and needlessly cruel, at one point flicking his sleeping daughter on the nose just for drunken laughs. Yet it is in the final ten minutes that things get really dark, and I wasn’t at all sure how far Sjöström was willing to push the drama, creating a genuine sense of tension and emotional turmoil. Expectedly, his performance here is wonderful.

The actress, Astrid Holm, who plays the Salvation Army do-gooder, Sister Edit, would star in Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (1922) the following year. (As a few points of random observation, Holm is a near dead-ringer for Jena Malone; also, Salvation Army women in 1920s Sweden apparently wore hats with the word “SLUM” on them.)

The Phantom Carriage is an excellent example of silent cinema, both within the horror genre and beyond, and its prayerful message is a sober meditation on our inevitable deaths: “Lord, please let my soul come to maturity before it is reaped.”

Grade: A