Movie Review – The Company of Wolves (1984)

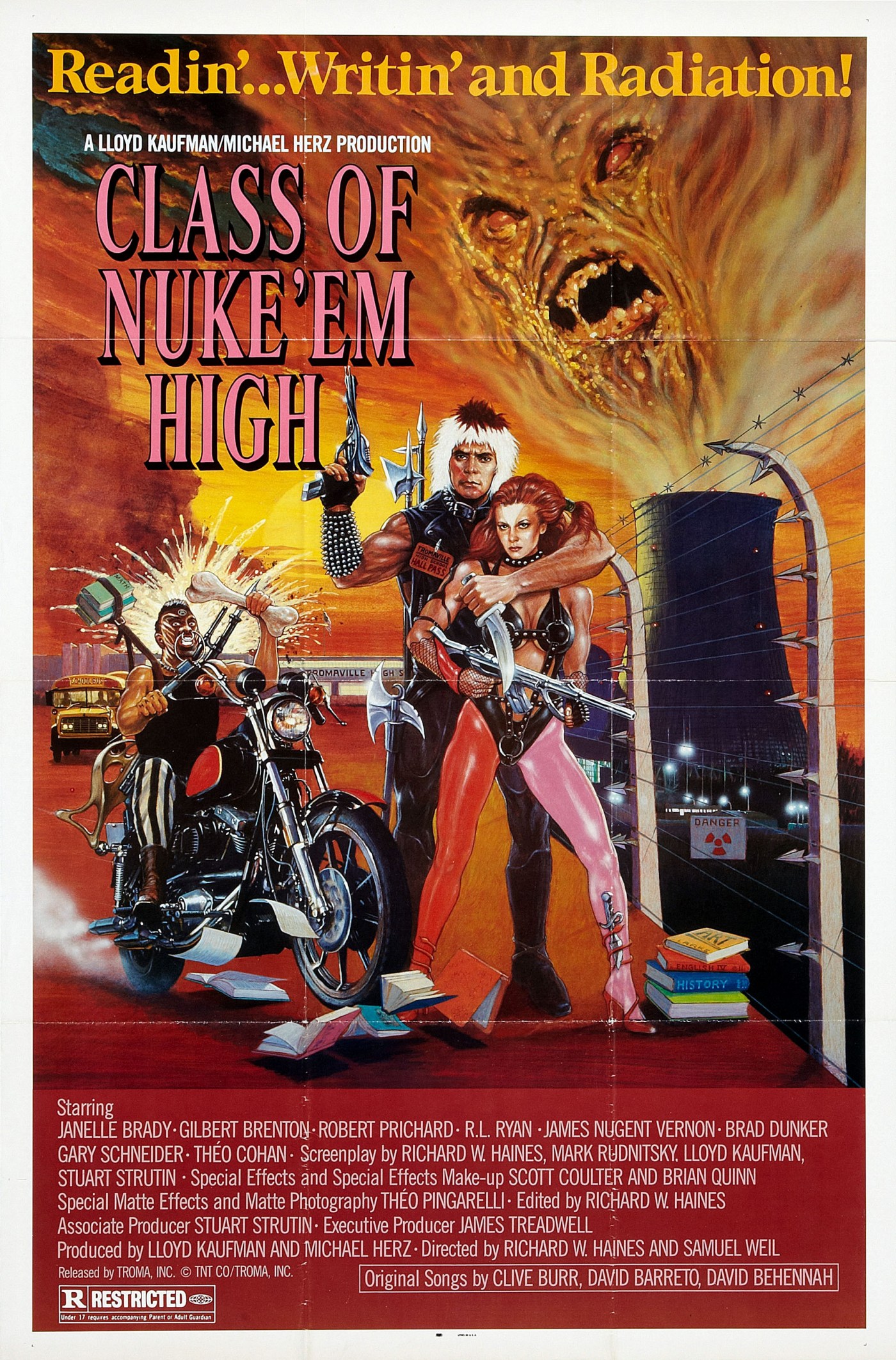

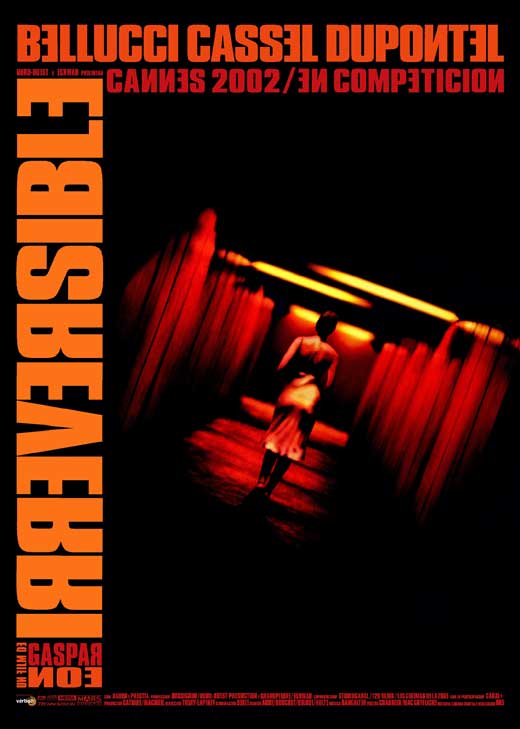

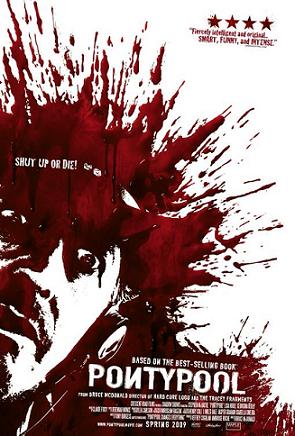

There are certain memories which are personally defining to one’s childhood, but are so specific to a certain generation that their children will never know them. For my grandparent’s generation it was buying candy at the Five and Dime. For me and my friends growing up in the 80s, there were the video rental stores. We’d wander the aisles of VHS tapes and feast our eyes on the covers. The horror section always beckoned me, and certain covers would burn into my brain and make me wonder at the nightmares that those spools of film contained, such as the looking skull of 1987’s Evil Dead II or the ponytail noose of 1986’s April Fool’s Day.

However, none captured my imagination more than 1984’s The Company of Wolves, showing Little Red Riding Hood looking at a man who has a wolf snout painfully protruding from his mouth. It fascinated me then but over the years, as I finally saw many of those films which had tempted me, I somehow forgot about it. Recently, however, I stumbled upon that image again while tumbling down one of those internet rabbit holes. There it was, those rental store memories flooding back. I instantly opened my Netflix account and placed the film in my DVD queue, moving it to the top.

The Company of Wolves is an early directorial effort by Neil Jordan, who went on to do 1994’s Interview with the Vampire, a film which had a significant impact on me when it was released, and 2012’s beautifully crafted though sadly underappreciated horror-fantasy Byzantium. The screenplay was written by Jordan and Angela Carter, adapted from one of Carter’s short stories turned radio play of the same name.

Wolves is very much a Gothic fantasy, rich with dream logic and symbolism. The film opens in the present day with a girl banging angrily on the door of her younger sister’s bedroom as her sibling sleeps restlessly on her bed wearing her sister’s lipstick. We immediately enter the younger girl’s dreams, which take place in a fairytale forest. We see the older sister running terrified through the gloomy wood, being accosted by the younger girl’s giant toys and then by hungry wolves which devour her, letting a smile play on the dreamer’s lips.

The dreaming girl is the framing device for rest of the film which takes place within the fantasy world, in both the forest and the village which it surrounds, and in the stories that the characters tell. And so we often times have a story within a story within a story. The narrative delves into the sexual subtext of Charles Perrault’s Le Petit Chaperon Rouge, first published in 1697. Unlike later versions of the Little Red Riding Hood story, this original telling was heavily moralizing. Red Riding Hood is tricked into giving the wolf directions to her grandmother’s house, who then eats the grandmother and convinces Red to crawl into the bed with him before eating her too. There is no woodsman in this version to save the day or seek vengeance. In case his readers missed the point, Perrault lays it out for them:

“From this story one learns that children, especially young lasses, pretty, courteous and well-bred, do very wrong to listen to strangers, And it is not an unheard thing if the Wolf is thereby provided with his dinner. I say Wolf, for all wolves are not of the same sort; there is one kind with an amenable disposition – neither noisy, nor hateful, nor angry, but tame, obliging and gentle, following the young maids in the streets, even into their homes. Alas! Who does not know that these gentle wolves are of all such creatures the most dangerous!”

The wolves in the film, and in particular werewolves, represent the carnal desires in men and serve as a warning to the main character, Rosaleen (Sarah Patterson), an adolescent girl on the threshold of sexual awareness. Perrault’s moralizing is echoed by her Granny, played by Angela Lansbury. She tells Rosaleen that some wolves are furry on the inside, cautioning her against the advances of amorous men. “Oh,” she states, “they’re nice as pie until they’ve had their way with you. But once the bloom is gone… oh, the beast comes out.”

The forest is a place of wonder, fear, and compelling curiosities, and is a stand in for sex. Her grandmother instructs Rosaleen to always stay on the path, for if you leave it you’re forever lost. When an amorous neighbor boy asks her to go walking, he declares that they will stay on the path, meaning a veiled preservation of virginity. When Rosaleen meets the sexually charged and handsome huntsman, he comes to her from the forest, a place of forbidden knowledge which she finds most tempting.

Rosaleen, like her sleeping counterpart, is becoming knowledgeable of her own sexual desirability. In a strange sequence fit for a dream, Rosaleen climbs a tree to hide from the amorous neighbor boy and finds a stork’s nest. In the nest is red lipstick, which she applies, and a hand mirror, with which she admires herself. The eggs in the nest crack open and instead of chicks we see baby figurines. All of this, I presume, is meant to symbolize her growing sexuality and fertility.

Though the werewolves are used mostly as symbolic warnings to girls about men’s passions, the film is not ready to adopt Granny’s perspective on things. Female initiative and power are strong currents through the narrative, as is the notion of not judging men solely by their sexual desires. When Granny laments that Rosaleen’s sister was “all alone in the wood, and nobody there to save her. Poor little lamb,” Rosaleen then asks, “Why couldn’t she save herself?” Later Rosaleen is talking to her mother about her grandmother’s views, to which her mother responds, “You pay too much attention to your granny. She knows a lot but she doesn’t know everything. And if there’s a beast in men, it meets its match in women too.” Rosaleen begins to adopt this very view, telling stories about a vengeful witch who displays female empowerment, and a harmless, misunderstood she-wolf. The men we hear about in the stories are carnal predators, but the one’s we see, particularly Rosaleen’s father, are fairly gentle men who are respectful toward the women in their lives.

The ending of the film, the specifics of which I will not spoil here, is ambiguous, though I believe it is all about breaking that barrier between childhood innocence and sexual maturity, shown metaphorically as the worlds of dream and reality violently crash together and the toys which played so prominent a role early in the film are left lying on the floor. Over this intrusion we hear Rosaleen reciting Perrault’s poetic warning:

Little girls, this seems to say

Never stop upon your way

Never trust a stranger friend

No-one knows how it will end

As you’re pretty, so be wise

Wolves may lurk in every guise

Now as then, ’tis simple truth

Sweetest tongue has sharpest tooth.

The Company of Wolves is not the first film to link female sexuality with bestial transformation, as we saw this in films such as Val Lewton’s 1942 production Cat People, and it is certainly not the last. 2000’s Ginger Snaps and 2011’s Red Riding Hood also link the two, this time adding the lupine aspects. The pairing of werewolves and female puberty is an obvious one as the cycles of ovulation and the Moon have always been symbolically related. Etymologically, the word “menstruation” comes from the Latin menses (month) and the Greek mene (moon), after all.

Though rated-R, I could easily see this film being shown to adolescent girls. The sexuality is present but tame by comparison to what is shown on television today. The horror is relatively light; the visuals focus more on a fantastical dread or gloom save for some gory transformation scenes, which appear inspired more by John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) than by 1981’s An American Werewolf in London or The Howling. It’s a shame that this film has largely been forgotten, just as I had forgotten it, as it is daring, impressive filmmaking which abounds with deeper meanings. Had it been rated PG-13, it may have become an important film staple in young girls’ lives.

Grade: B+